Aave — Part I

Introduction to Lending Protocols

A lending protocol is a set of smart contracts that facilitate loans against a pool of user-supplied deposits.

The individual mechanisms are simple:

A depositor can supply an asset to the protocol

A depositor can withdraw their previously supplied asset, plus accumulated interest, up to the unborrowed amount currently held by the protocol

A depositor can also be a borrower, and can create a loan against some other assets

Borrowers must repay the full amount of their loan, plus accumulated interest, to close their loan

The value of a deposit must exceed the loan amount at the time of generation, a practice known as “overcollaterilization”. This provides a safety margin so the protocol and its users can react appropriately to fluctuating collateral values.

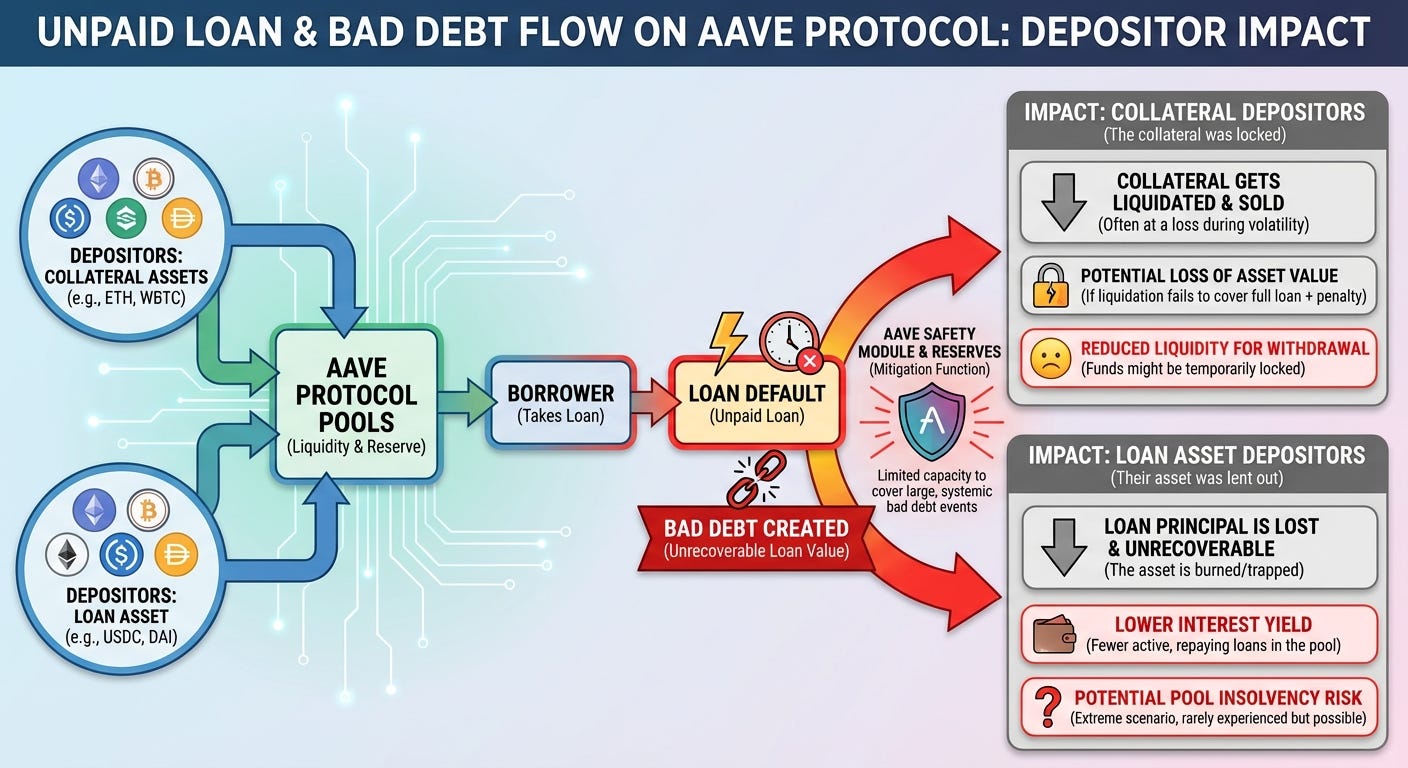

Bad Debt

Since the protocol distributes assets deposited by its users, there is a risk of insolvency if loans are not repaid.

For a given loan, if the value of its collateral assets falls below the value of the loaned assets, it is unlikely that the borrower will repay it — a rational borrower would prefer to hold the loaned assets instead of returning it for their devalued deposit. Loans like this are labeled “bad debt” because they create unsatisfied obligations to two groups of depositors — one supplying the collateral asset, and one supplying the loaned asset.

Bad debt hurts both groups because a deposit asset can only be withdrawn up to the unborrowed amount — that is, only the amount of an asset held by the pool and not currently given to a borrower.

In the case of excessive bad debt, a lending protocol can experience a “bank run” event where only a fraction of users can withdraw unborrowed assets, and everyone after is unable to withdraw.

Liquidations

Since bad debt is dangerous, the protocol needs safeguards and mechanisms to reduce or remove bad debt.

Some protocols manage a separate asset reserve that can make depositors whole following a liquidity event. This is outside the scope of our study, so we won’t concern ourselves with this.

The first defense against accumulating bad debt is to incentivize third parties to liquidate (repay) unhealthy loans. As the asset value ratio of collateral vs. borrowed falls, liquidators are incentivized to repay a portion of the loan in exchange for an inflated share of the collateral.

The primary effect is reducing the outstanding obligation to the loaned asset’s depositors. But the secondary effect is increasing the outstanding obligation to the collateral asset’s depositors.

These effects seemingly antagonize the two groups — the loaned asset’s depositors are being made whole at the cost of the collateral asset’s depositors!

However, remember that every loan is overcollateralized. Thus each collateral asset across the protocol should have a net positive amount of pooled liquidity. This extra balance is what pays for the liquidation incentive, and lending protocols often implement variable interest rates to encourage users to shift their behavior towards either deposits or borrowing.

Aave

According to DefiLlama, Aave is the largest lending protocol by total volume locked (TVL).

There are three major versions of Aave, presented below with a link to the white paper, date of first deployment to Ethereum mainnet, and a snapshot of TVL:

V1 — Jan 2020, $10.3 million

V2 — Dec 2020, $187.8 million

V3 — March 2022, $30.3 billion

Aave V3 manages a majority of current lending activity, so we will focus on it. V3 is deployed to several chains, so the strategies we develop here will be portable.

Moving Forward

We are here to find profitable opportunities, and the primary way to do this on Aave is to act as a liquidator.

But before we can develop a liquidation strategy we must study: how deposits are managed; how loans are created, repaid, and closed; and how loan health is tracked.

The next entry in the series will cover the most important smart contract on Aave — Pool.